This summer included the hottest July ever recorded on the planet. Wildfires have exploded across Canada. Europe is also experiencing extreme weather. A study published in Nature says a current in the Atlantic Ocean crucial to stabilizing the climate is likely to collapse between 2025 and 2095.

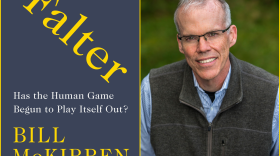

Bill McKibben is among the world’s preeminent environmentalists and teaches in flood-ravaged Vermont. A prolific writer, nearly 30 years ago he published “The End of Nature.” WAMC North Country Bureau Chief Pat Bradley spoke with McKibben and asked if we are now seeing the end of global environmental stability:

We're definitely seeing what climate change, what the climate crisis, looks like in its early but very real stages. It's been a very, very scary summer. I think especially for scientists because the change that's happening is coming quite quickly and faster than anticipated is the kind of motto of climate scientists, I'm afraid. And this summer is demonstrating that, since this is an experiment we haven't run before, we should be prepared for surprises. So surprises include the fact that the oceans, particularly the North Atlantic, are way, way, way higher, five standard deviations higher, hotter. That we're seeing, extensive and unpredicted melt of the sea ice in the Antarctic. And the effects on land are very large. You know, those forest fires in Canada have burned more acreage already than any total year ever in Canadian history and we're only halfway through the summer.

You mentioned the concerns about the oceans and the ocean currents. We've heard about that along with the rising ocean temperatures. How big a factor and how does that factor into what we're experiencing or is that something that's yet to come?

Well, there's several things going on here. We are at the beginning of an El Nino period. It's just kind of clicking in now in the Pacific and that will warm the planet as these always do. But that comes, each time we get a new El Nino now we get a new global temperature record because it's coming on top of the heat that we're trapping with all the fossil fuels that we've burned. So we start from a higher place each time. It's like walking up a set of steps. And this step, seems the riser on this step seems larger than any of the ones we've encountered before. The temperatures really, really went up dramatically in June and July. July was the warmest month we've ever measured on this planet. And as you know it featured the hottest days we've ever measured on this planet, one after another. Those records go back we think 125,000 years, something like that. We think that's about the last time when it could have been this hot on our planet. And we're starting to see the results. I mean these incredible heat waves, these melt events, these wildfires and since warm air holds more water vapor than cold these downpours and deluges like the one that's you know, come to my town in Vermont now a couple of times this summer producing landslides, closing roads, destroying homes, on and on and on.

You founded 350-Vermont to try to get people aware of what seems like a minor change in global temperatures have a massive impact. How much does a degree or two in record temperature changes make?

Well, so first of all, I should just say if I founded three fifty.org, which works all over the world. We've organized 20,000 demonstrations in every country on earth except North Korea. And the Vermont chapter is a wonderful and active one. But I confess I do very little to help the good people who run it. The rise in temperature, think about it in other units Pat. The amount of extra heat that we trap in the narrow envelope of atmosphere in which we live, the amount of heat that we trap there every day, because of the carbon that we've poured into the atmosphere. It's the heat equivalent, again every day, of 400,000 Hiroshima-sized explosions. So when you get that figure in your mind then you start to understand how we've been able to melt most of the sea ice in the summer Arctic or raise the level of the oceans. That's a lot of energy that we're adding to this closed system.

Can climate mitigation actions be effective at this point and what will it take? Can we reverse the effects that we're seeing now?

Well, I don't know about reverse. I think the big question at the moment and probably for your lifetime, my lifetime anyway, is going to be can we begin to slow down this to keep it from getting too much worse. So far, we've raised the temperature of the planet about 1.3 degrees Celsius, not neigh on two degrees Fahrenheit. But on a path to raise it five or six degrees Fahrenheit and three degrees Celsius. If we do that, Katie bar the door, I mean you know, that's just too much change. We won't have civilizations like the ones we're used to having. So the job is to try and arrest that slot that rise in temperature as fast and decisively as we can. We have the tools that we need to do it. Scientists and engineers in the last 10 years have lowered the price of solar power, wind power and the batteries to store that power when the sun goes down or the wind drops. They've lowered their price by 90%. We live on a planet where the cheapest way to make energy is to point a sheet of glass at the sun. So if we went all in, if this is all that we worked on, in the same way that we, you know, building tanks was what we worked on at the beginning of World War Two, then we could make a big difference in a short time. So far we're not going at all in. We're going after kind of half-heartedly, lackadaisically. And that needs to change if we're going to make progress in the short amount of time that physicists still give us. They've told us that if we want to stay anywhere near the targets we set in Paris just eight years ago we have to cut emissions in half by 2030. And, you know, by my watch 2030 now is six years and four months away so we better pick up the pace.

Bill McKibben, you mentioned that if nothing changes we won't have civilizations that we're used to having. If nothing changes, what do you expect the new global climate to look like?

Very hot and filled with surprises. One of the ominous things of this summer was a series of papers indicating that we may be closer than we’d thought to the shutdown of the Gulf Stream. As we change the salinity of the water in the Atlantic those kinds of changes are so big that it's hard to kind of guess exactly what they do except that they would produce extraordinary chaos across our societies. So the goal is to slow things down so that we're moving instead of in, you know, double time what we're moving now maybe we could get this to move in slightly slow motion so we have some chance of catching up with it.

Bill, you also mentioned that we've got six years and four months before this 2030 deadline, for all intents and purposes, and that action really needs to be taken. But we take a look at some of the climate change deniers, some of whom are in government, and they look at the heat waves and shrug it off saying well, it's summer, it's supposed to be hot. How do we break through that?

You know, the actual real serious denial you can't break through because it's usually informed either by ideology or by financial ties to the fossil fuel industry. But we can get people who are somewhat concerned to be much more active. The polling indicates most Americans really are pretty worried but not very many are really out in the streets where we need them. That's why among other things, in the last year or so we formed this group Third Act for people like me who are over the age of 60 to get them really engaged in this fight. And it's been going great. We now have chapters in most of the states of the union. Many, many, many tens of thousands of older people engaged in this fight. So you know, tell your grandparents about it.

You just returned from Europe and we are hearing about heat waves and wildfires and floods there. What did you hear and see from Europeans?

Well, much the same. The Europeans are working hard to try and change their energy mix and that's what I was over there talking about. They're rolling out heat pumps, for instance, electric heat pumps to replace furnaces very quickly. And a lot of that's because of the climate crisis. And a lot of it's because they're trying to blunt the power of Vladimir Putin who has been, you know, abusing his control of oil and gas as a weapon for many, many years now and they're tired of it. So there's some real progress being made there.

What species, including humans, do you think will be able to survive this changing climate?

Well, I sometimes think that if somebody is watching from a distant planet through a telescope measuring what we're doing to our atmosphere they might conclude that we had embarked on a big planet wide mosquito ranching-operation. Because if there's anybody who likes a warm, wet planet it's mosquitoes and at least in this part of the world ticks seem right behind. So that's the fauna to place your bets on I think going forward.

This has been for several years, and it seems to be getting even more so, overwhelming for the individual. So how and how much difference can an individual make at this point?

Well, look, we're past the point where we're going to make the carbon math work one Tesla at a time. Though, doing things in your own life is important, the most important thing an individual can do is be a little less of an individual and join together with others in movements large enough to make a difference. That's why we started three fifty.org, or Third Act or you know why there's a Sierra Club or all the other groups that try to bring people together in large enough numbers to really leverage their efforts to make more fundamental change.

So I take it you believe we're not beyond the point of no return?

Well, I confess sometimes this summer it's felt like we're very much in the rapids now and you can kind of hear an ominous rumbling from around the next bend in the river. But the best science indicates that we still have a window, one that's closing, but it's still there and real if we move fast. So this is our test and our challenge. We’ve got to move fast. And that's why I spend my life working on this and I'm always gratified by the number of other people who do the same.

Bill McKibben is a Distinguished Scholar in Environmental Studies at Middlebury College. According to his official biography, biologists recognized his career by naming a new species of woodland gnat in his honor in 2014.