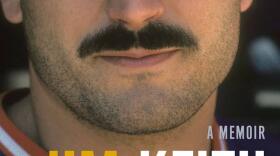

Jim Kaat’s new memoir is called “Good as Gold: My Eight Decades In Baseball," a time that included driving in two runs in the 1965 World Series as a pitcher. Such changes to pitching and hitting over Kaat’s long life in baseball are just some of the developments he’s not thrilled about.

Kaat spent 25 years in the majors, pitching in the 50s and the 80s, and never really left, also working as a coach and broadcaster. And now, at age 83, the 16-time Gold Glover and winner of 283 games is finally being inducted into the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown in July.

I take it from reading your book that you have an excellent memory for games and situations. So what was it like driving those two runs in?

Well, what happened is Ron Perranoski was the pitcher. And this is kind of a cute side story: Rod later was traded to the Twins, and we were teammates. And there were men on first and second with two out. And Frank Quilici was the hitter. I was on deck. So he balked on purpose. So the runners advanced to third and to second. And then he walked Quilici intentionally to get to me, which was logical being a pitcher and a lefthander against a lefthander, and I believe he'd gotten me out once before. And then to get a single up the middle and knock in two was pretty rewarding. And we got to talk about that later when we became teammates in 1969.

We don't see a lot of pitchers hitting anymore. Obviously the designated hitter going to both leagues is changing the sport. What was your approach to hitting?

Well, when I was a young kid, like I think a lot of us that played in the 60s in the major leagues, we were baseball players that just happened to be pitchers. We were trained and taught to learn how to bunt, to learn how to make contact, we played a lot of a forgotten game now called pepper. That was all part of what we did, learn to run the bases, learn to slide. And so as I advanced through high school ball and college and minor leagues and major leagues, I was trained to do that. And I understand now why they need the designated hitter because even in Little League, pitchers don't hit. Kids don't hit if they're just pitchers. And so they're never trained to do that. Which is sad. But that's the way it is today and probably a good thing they have the DH even though I was never a big fan of it.

Being a hitter in your career, did it give you a different appreciation for what other pitchers could do?

Definitely, one of the things I looked at when I was facing another pitcher is what kind of a hitter he was. For example, Gary Peters, who was a lefthanded pitcher with the White Sox was a very good hitter. Dean Chance, who was a good pitcher with the Angels, was not a good hitter at all. So I always felt that if I was a better hitter than the pitcher on the other team, could handle the bat better, that was an advantage. And the goal that I was taught by Eddie Lopat and Johnny Sain, two of my pitching coaches, was try to be responsible for one run a game. You either bunt a man over or you knock a man in or there's man on second and nobody out and you hit a ground ball to advance him to third. Some way at the end of the game, you can say you were responsible for your team scoring one run, because then the other team had to score two to be ahead of you. So it was an advantage being able to handle the bat.

And also the way that pitchers were used back then, you knew you are going to get two, three, four at-bats.

As long as you were pitching well, yes. I mean, you had those games where you got knocked out early, but certainly pitching anywhere from the eighth to the ninth inning and hopefully a complete game, you knew you were going to get four at-bats. And most of the time in those days, I'd say three of the four were going to be against the same pitcher. So that was also a bit of an advantage versus today's game where it's so specialized that hitter are facing a different picture almost every at-bat.

Well, I have a lot of questions for you about different points in your career. But before we go back, I mentioned in the introduction that you've been elected to the Hall of Fame. In and what many would say it's an overdue induction. What has it meant to you to one, learn that news, and then look forward to your induction ceremony this summer?

Well, it's been a very humbling and rewarding experience. I never really realized the magnitude of the attention that it creates from friends that knew I was a baseball player for years, and all of a sudden, this Hall of Fame addition has a cache to it, where, you know, it's just creating so much attention and in a good way. I mean, I'm humbled by it, but it's been so exciting to connect with people, and many of them, of course, will be in Cooperstown. And it's been, you know, overwhelming in terms of attention, but you know, it's rewarding. It's something that I really didn't expect anymore at this age. And all of a sudden it happened, and I'm so thankful for it.

Did you feel that you belonged?

Well, I thought the reason I was not voted in by the writers and it took a while is that I never considered myself a dominant starting pitcher like Seaver, Koufax, Marichal, Gibson, most of the starting pitchers that you see in the Hall of Fame were dominant pitchers. I did what I did over a long period of time. And I also was a relief pitcher for several years near the end of my career. So from that standpoint, I didn't really know. I think I could make a case by looking at some pitchers that yes, my records might have been worthy of that but I'm grateful that the Golden Days Committee this year took a look at it. And looked back and compared me to some of the other starting pitchers and rewarded me for consistency and longevity and dependability.

How were you able to stay in baseball as long as you did?

Well, I think I was blessed with a durable arm and a durable body and we had an expression years ago, you never really learned how to pitch until you hurt your arm. And I was a dominant pitcher in 1959 in the Southern League. I had set the strikeout record with 19 and then I struck out a few more early in the next game and I injured my shoulder. I just felt something in my shoulder that wasn't right. We didn't have MRIs or the kind of treatments and technology they have today.

And when I came back from that I never was really the same power pitcher. So doing that early in my career I had to learn to as a couple of my coaches had told me give hitters enough chances to get themselves out. A Sandy Koufax, a Sam McDowell, a Bob Gibson, you know, names of some power pitchers in that era, they could get hitters out with their raw stuff like Nolan Ryan would do during his time and say a Max Scherzer does today. But they taught me that you have to give a hitter an opportunity to get himself out because you can't overpower them. And you do that with movement, control, change of speeds, and motion. And I learned to do that at an early age. I was lefthanded, which was unique, teams are always looking for lefthanders. I was able to say pretty much injury free. And I had a motivation every year to continue to be able to pitch at that level. And the combination of all those things is probably the reason why I was able to do that for you know, almost 25 complete seasons.

You threw so many more innings and so much more frequently. I mean, you were on three days’ rest for parts of your career. How do you think that factored into your mindset about pitching? And I ask that, you know, knowing that today in the game, pitchers are on very strict pitch counts. We saw Clayton Kershaw come out of a game with a perfect game on the line in the seventh inning. So the way you did it, and the way it's done today, are just completely different. Was it just the mindset that you knew you had to get late into the game and you had to go on Friday that kept you out there like that?

Well, I think it was the training. I think we were trained in the minor leagues and going back to amateur ball, I remember in American Legion baseball as a 16-year-old, I pitched a seven-inning game at 11 in the morning and another one at 4 in the afternoon. That wouldn't happen today. But I remember in 1958, pitching for Jack McKeon in Missoula in a 125-game season, I think we had about eight pitchers on the staff. So we pitched every four days.

And then because there was a lack of lefthanders, I may even be used in between starts in relief. And so, you know, pitching 225-plus innings in the minor leagues gave me the foundation to do that in the big leagues, and unfortunately, today's pitchers, they have the ability to do that but because power is so important to pitching today, they're tougher on their arm, it's much more difficult. We see so many more arm injuries. They hothouse the pitchers today. ‘OK, you've thrown 35 pitches today, that's enough, ice your arm take some time off.’ So they never really build up their legs, their arm, their entire body to go as long into a game as they could. And I'm really disappointed in that because Max Scherzer, Clayton Kershaw, we could go on and on with the list. Madison Bumgarner in his era was a standout. When he was dominant, they could do it. But they're not trained to do it. And I think it's robbing them and the fans of seeing these elite starting pitchers go head to head well into the end of the ballgame and in hopes of doing it in the ninth inning.

Are there any pitchers working today who you identify with because they do have the approach that you took with seeking soft contact and that kind of thing?

I don't think there's many today. I haven't seen a lot of Kyle Freeland from the Rockies. Most of the pitchers today, power is a prerequisite. If you're a youngster in high school or get into college, you have to suddenly light up the radar gun or scouts are not even going to look at you. So I can't think of any. When I was doing Yankee games back in the 90s when Andy Pettitte came up. I always thought that that was the style of picture that I was. Andy, who was not an overpowering pitcher, yet he had a good fastball and a good curve, added a cutter. So my fastball early in my career was still my number one pitch. But it was a fastball with movement, which today they would say Well, that's a two-seamer, a sinker. We didn't we didn't care what they called it, but we just wanted some movement on it. So I still relied on the fastball. Even though I wasn't overpowering. I can't think of any. I mean, Clayton Kershaw has a lot more weapons than I ever did. I'd have to I'd have to look at the rosters of some major league teams and find out who kind of does pitch the way that I did.

It occurs to me that it often happens near the end of their career. I mean, Kershaw himself is an example. They don't have the lights out speed that they once did… Maybe Bartolo Colon a few years ago. So now they've got to get creative.

Well, that's true. And that's what I had to do early in my career. I mean, I couldn't just pitch the way I did in 1959 in the minor leagues, when I could just overpower hitters and even in 1958 in Class C ball at that level, I had, I think, 245 strikeouts in 225 innings, something like that. So I knew I couldn't pitch like that. So I developed that early on. Some pitchers, as you mentioned, are doing it late in their career, when they're forced to kind of change their style.

You're also known as one of the best fielding pitchers ever. What was your approach to defense and what made you successful in that facet of the game?

You know, I was hoping I could have my boyhood hero at my induction. He was planning to go but he's 96 years old. His name is Bobby Schantz. He was the American League MVP in 1952. And when I was a young boy, baseball was a radio game. And I could listen to eight games on a Sunday afternoon, the Tigers, Cubs, White Sox, and later the Braves all played doubleheaders.

Sorry to interrupt. I just want to say you were growing up in a small town in Michigan, so you were geographically located to get a lot of radio.

Exactly. So when the A's were playing the White Sox, the White Sox announcer would say, well, here's Bobby Shantz, best fielding pitcher in baseball, he lands on the balls of his feet, he can go left, he can go right, he's ready for a ball hit back at him. I would go into my backyard off the garage with a tennis ball and I mimicked Bobby Schantz. And when I got to the big leagues and went through some of these training exercises for pitchers fielding drills, the coach said, ‘Kid, you look just like Bobby Schantz.’ So that was quite a compliment. And that's where I got it from. And Bobby was a pitcher that I modeled my motion after.

And even though he will not be at your induction, there is a photo of the two of you together at a Gold Glove ceremony in your new book. It must be amazing to have someone be your idol for this many years and still have the chance to be in touch with them.

Yeah, that is that is quite an honor. And I mentioned that at the Rawlings Gold Glove dinner three years ago. Mike Thompson from Rawlings had called me and said we're going to give an award this year to one of the first Gold Glove winners when we started giving them out in 1957. He said, ‘Have you ever heard of Bobby Schantz?’ I said ‘Heard of him, he's my boyhood hero.’ So that's how that happened. And when I got up to give him the award, I said to the audience, how cool is it for at the time an 80-year-old to give an award to his boyhood hero who’s 93. And that's why it would have been such a thrill for Bobby to be there, but I can fully understand. I'm just happy that I think he'll be in the TV audience because I want to acknowledge him anyway.

Part of your story is about the time when you were a pitching coach for Pete Rose, and you didn't spend a lot of time as a pitching coach. How come you didn't want to stay with coaching?

Oh, it isn't that I didn't like it. But Pete had always told me when we when we competed against each other, I found out, that if he got a manager's job, he wanted me to be his pitching coach. And I was honored by that. So when he got the Reds job in late ’84, I went in there and did all of ’85. And then in in my era, if there was a rain delay, they would call a player up to the booth to kind of kill time and tell stories. And I had a lot of producers of TV and radio and said, Boy, you ought to get into this when you're done playing. So suddenly, I began to get calls from different agents and producers, for example of the Yankee games, Don Carney that said you should consider getting into broadcasting. So I found out that could be a very long career if I was able to do it well, so I decided to leave coaching after ’85 and was able to get the Yankee broadcast job in 1986. And got some great training. I worked with Bill White and Phil Rizzuto, Scooter. And Bill to this day is still my broadcast mentor who taught me more about broadcasting in those early days, that really helped me.

I had to laugh reading your book as someone who grew up as a Yankee fan watching Rizzuto’s broadcasts that you got a trial by fire because he left you hanging one time in the seventh inning early on.

Yeah, we were in Cleveland. It was a cold, bitter night, which it can be in Cleveland in April in that old stadium they call the Mistake by the Lake. But we had a three person rotation, so would be Bill and Scooter, then Scooter and Bill and then Scooter and I and Scooter and I were the last three innings. And so when I got into my seat, he said Kaat, I'll be right back. I gotta go to the men's room. Well, he never came back. And as the inning started, I think I said, Well, here's Joe Carter, I'd never done play by play before. I began to describe the action. And Don Carney, the producer, on the talkback button, said Where's Rizzuto? And I said he'll be right back. He went to the bathroom. Well, he never came back because it was cold. And he just went back to the hotel. And I did the last three innings of that game by myself.

When someone has spent as long as you did in competitive sports like baseball, you were a pitcher for so many years, then coaching for a while. What happened to your competitive drive once you weren't directly affected by wins and losses every day?

Well, I think I knew that I still had to find something to do. You know, I was fortunate I was into the game. I went to spring training at age 45. And I had to find something to do. And then Pete offered me the coaching job. So that was good to stay in touch with baseball. And then I think looking around for something to do, I didn't know exactly what I would do, but the announcing thing just kind of fell into my lap and that satisfied. I don't know if you would say a competitive edge. But it motivated me to do work. To work in the game of baseball and to do something that was productive. And so that's where announcing came in. And I'm so fortunate that this year is my 63rd season in being involved with Major League Baseball one way or another, either as a player coach, or announcer.

You're also an avid golfer, are you competitive on the golf course? Or is it fun?

It's become fun, I would say, early in my retirement days, I was competitive. I'm fortunate to be a good friend and play a lot of golf with Bill Parcells and Coach Parcells cannot let the competitive gene go. He just battles on that golf course. It bothers him at night if he hasn't won the match that day and I say, ‘Coach, we worried about that too long. We just have to be out here and enjoy the recreation and do it for fun.’ And so right now, as I say to some young players when we finish and they say, Well, how'd you play today? I said, Young man, here's the deal. Never ask a player over 80 how they play, just ask them did they play. So I'm fortunate that I can still get out and play.

How are you feeling?

I feel fine, you know, the usual aches and pains at age 83 that you wish your body could do it can't do anymore. But I feel good when I, unfortunately run into teammates, colleagues and hear about the issues that they have. You know, the mental health is such an issue now. So I feel very fortunate to be able to do what I do physically and mentally and stay involved in baseball and be an active citizen.

Just a few more things. You have a lot of issues with today's game, the way it's played, the slow pace and that sort of thing. What do you think the major changes are that baseball should make?

Well, I was encouraged to hear that the pitch clock that they're using in the minor leagues, 14 seconds with nobody on base, I believe it's 18 with a man on base. For some reason, it seems to have motivated hitters to get back in the box sooner and start playing and competing. And they've shaved, I believe, some 20 minutes off games. Now, if that did not work in the major leagues, I think that's coming. I hated to see a pitch clock. But if that's what happens and it'll work, why that's a step in the right direction. I always thought that today's game should be seven innings. And they should deaden the ball, soften the ball a bit, and maybe go to three balls you walk, two strikes, you're out. We used to play intersquad games like that in spring training just to keep the game moving. And when I look at Clayton Kershaw, for example, that had to come out after six innings, because that's the way they're trained to throw X amount of pitches, we would have pitchers with fewer pitches, teams would have fewer pitchers on their staff. And I think we'd have fewer injuries, but maybe the pitch clock at least, is addressing the pace of play.

How long was it between your pitches when you were pitching? Do you know?

I really don't. I mean, I've heard and I just can't buy into this, but I've heard some physical and mental reasons why you have to take at least 12 seconds. That it takes that long for your brain to process what you're going to do next. Then I've heard, which I don't believe in, that if you force these pitchers to throw not as much time between it's a danger, they might hurt their arm. Well, I had on my glove in Magic Marker ‘Study long, study wrong.’ I couldn't wait to get the ball back and quickly deliver the next pitch because I felt like it made the hitter uncomfortable. And I've had hitters like Brooks Robinson in my era that told me it did.

So I think the quicker you can work, it's certainly not a not going to be a danger to your to your arm to throw another pitch that soon. And I think the thought process is, I decided what the first three pitches were going to be when I faced a hitter. If the first pitch was a strike, I knew what I was going to throw next. It was a ball, I knew what I was going to throw next. So those kinds of things I was always prepared ahead of time. And I just think the quicker you work, the less time the hitter has to get comfortable, the more effective you can be.

What do you think of the idea, which seems to be coming, of robot umps or some approximation of robotic umpires?

Well, it goes right along with what's happening in sports today: get the game right. There's good examples of that when even going back to the 1985 World Series where there was a famous blown call that cost the Cardinals the World Series and then Jim Joyce, who was a very respected umpire, missed a call that Galarraga would have pitched a perfect game in Detroit several years ago.

So I can understand that part. Get the call right. But I still liked the human element. I liked the fact that I made mistakes as a pitcher, umpires are going to make mistakes, you have to live with them. We knew from a ball-strike standpoint that if Ed Runge was behind the plate, the plate was about 20 inches wide. He gave me a little extra on either side. His motto was hey, people didn't come to see you walk. Swing the bat. If I had Eddie Hurley behind the plate, the strike zone was big as a cracker box. So you knew that you had to adjust accordingly. So I still like the human element of the umpires.

I'd like to end on something of a lightning round. Who was the toughest batter you ever faced?

Al Kaline.

How come?

Well he was a right hand hitter. Batting champion when he was 19. I just couldn't get him out. He was very comfortable against me. Hit 10 home runs, that's more than I gave up to any other hitter. And he was just a hitter that I had one good game against him. It was my 25th win in 1966. And he struck out three times. Tony Oliva hit a home run the ninth inning and we won the game 1-0. But that's the only game I can remember that I had more success over Al than he had over me.

What was your favorite team that you played on?

I'd say the 1982 Cardinals, it was my 24th and last complete season in the big leagues. And we hit 67 home runs as a team, stole 200 bases. We did it with speed, pitching and defense. And it was kind of a throwback team that you'll never see again. But that was a very exciting team to be a part of.

What was the favorite team that you've had as a broadcaster to watch?

I would say the 1998 Yankees and actually that entire stretch when I got the Yankee job thanks to Tony Kubek from ’95 to 2006. The Yankees were good every year. But in 1998 they had that combination of hitting, starting pitching, relief pitching, made productive outs and sacrifice flies played good defense. I think they won 120-some games when you count postseason play. That was that was the best team to follow. It was a real treat to watch them every day.

Thanks for all the time and congratulations.

Thank you, Ian. I appreciate the time and always a pleasure to talk with you.