The annual federal defense bill, known as the National Defense Authorization Act, does not include certain provisions that would address PFAS water contamination. A Washington-based nonprofit group accuses Congress of caving on cleaning up the toxic substances.

While not final, it appears that the NDAA leaves out some PFAS-related bills that the Environmental Working Group’s Scott Faber says would signify substantial progress in regulating the class of toxic per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances.

“I think everyone agrees that we, people shouldn’t have to worry about whether or not they’re getting a mouthful of PFAS chemicals when they go to the tap,” Faber says. “So it is very frustrating that our elected leaders could not work together and iron out the details so that we can turn off the tap, if you will, so that we can begin to reduce ongoing releases of PFAS pollution and so that we can begin to clean up legacy contamination.”

Faber is senior vice president for government affairs at EWG.

“PFAS pollution has now been detected in the water of nearly 1,400 communities — that’s one-thousand, four-hundred communities — and more than 100 million Americans are likely drinking water contaminated with PFAS,” says Faber.

Democratic Congressman Antonio Delgado, of New York’s 19th District, says the final NDAA authorizes critical defense programs and includes a number of other provisions that make the U.S. safer and more equitable, including a pay raise for troops, additional supports for military families, and climate change protections. Delgado’s statement continues that, unfortunately, there was a huge opportunity to make similar progress for communities like Hoosick Falls and Petersburgh grappling with PFAS contamination. Again, Faber.

“And a bill that fails to clean up legacy PFAS pollution falls far short of what people in Hoosick Falls, New York; Louisville, Kentucky; or Wilmington, North Carolina and all the other communities contending with PFAS contamination expect from our elected leaders in Congress,” Faber says.

PFOA and PFOS, which are PFAS substances, were found within the last five years or so in drinking water in Hoosick Falls, Petersburgh and Newburgh. In the case of Newburgh, the contamination stems from Stewart Air National Guard base as the result of the historic use of firefighting foam, and where the Army Corps of Engineers constructed a temporary filtration system. Faber specifies which provisions have been left out of the NDAA.

“We are very disappointed that our congressional leaders appear to have decided to remove provisions that would require… that would end unlimited discharges of PFAS into our drinking water supplies; that would require water utilities to filter PFAS out of our tap water; and, perhaps most importantly, would designate PFAS as hazardous substances under CERCLA, our Superfund law,” says Faber.

Meantime, while a provision requiring cleanup of most PFAS contaminated sites under the federal Superfund law apparently did not make the final cut, Environmental Working Group Legislative Attorney Melanie Benesh says a related measure did.

“There is a provision that, I think Scott mentioned, that would require the Department of Defense to enter into cooperative agreements with states,” says Benesh. “That was included in both the House and the Senate versions that passed out of their respective chamber, and it’s our understanding that that is still in the conference version, so that does give states a little bit more leverage to work with DoD to clean up contaminated sites in their own states and potentially enforce state cleanup standards for the states that have them, but it’s certainly not as comprehensive a tool as Superfund designation would be.”

Meantime, Faber mentions some progress in the NDAA.

“New requirements to monitor for PFAS in groundwater and tap water; require reporting of releases of PFAS by manufacturers; and finally end the DoD’s use of fluorinated foams,” Faber says.

And, he says, a bill that New York U.S. Senator Kirsten Gillibrand introduced earlier this year seems to be in the final version. The bipartisan PFAS Release Disclosure Act would require the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to create a process to add PFAS chemicals to the Toxic Release Inventory, a centralized database of environmental releases of toxic chemicals.

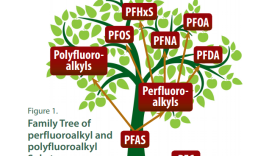

In addition, Faber says a bipartisan bill that requires the EPA to designate all PFAS substances as hazardous substances will be considered by the full House in January. Co-sponsors of the PFAS Action Act include New York Congressmen Delgado and Sean Patrick Maloney.