Julia Indichova is the author of "Inconceivable" and "The Fertile Female" and the founder of FertileHeartedHuman.org. "One-Heart Revolution: The Perils of Positive Thinking" is due in the spring of 2019.

Exquisitely Sane

I never saw my mother cry. She kept a safe distance from the incoming tide of sorrow, which, left unchecked, might have washed away her two new children, her husband, her brand new second life.

She never mentioned the day the order came for every person of Jewish descent to report to the two brick factories at the edge of her town. In her stories her son was alive, taking a daily pre-dinner walk through the neighborhood, playing a game of multiplying the numbers in the small square plaques next to each entryway.

For my mother grieving was not an option. And after all these years of attempting to understand the forces that have shaped my life, part of me still doubts the legitimacy of my own claim to grief.

I wasn’t there. My brother is just a fine-featured little boy in a photograph. My grandmothers gaze into the distance unaware of the granddaughter probing the picture for some sign of recognition. I will never know the sound of their voices.

To be fair, I did serve my time with analysts of varied persuasions. Some were helpful. Others were more mystified by my obsession with the gruesome subject of Hitler’s Final Solution than I was. Hardly any of my American friends have had direct contact with the horrors of war. It was simply not a subject relevant to their daily list of concerns.

Then one ordinary Tuesday in September of 2001, warfare became chillingly relevant to everyone I knew. That morning, the fearsome vulnerability I’ve lived with much of my life, was suddenly everyone’s reality.

In the weeks that followed, the harrowing fate of the victims, the sheer enormity of suffering, the anthrax scares, and the powerlessness I felt in the face of it all, became debilitating. During the sleepless nights, I combed through news stories online, and kept feeling I should be doing something.

After all, the hijackers were doers. They acted on their convictions. They showed us through the clearest, most personal act their view of reality.

What about me? How should I voice my views, act my convictions?

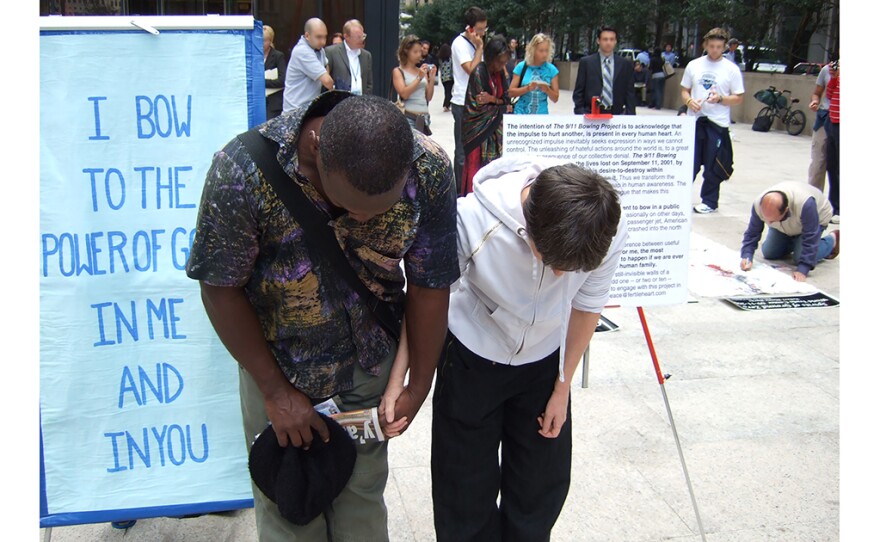

Every now and then in the midst of my daily errands, I imagined standing in the middle of a busy street with a mammoth sign that says: I BOW TO THE POWER OF GOOD IN ME AND IN YOU. I wanted to speak about the hater in me. I wanted to acknowledge the impulse to strike back, the wish to hurt those who hurt me, which remains within me despite years of mental detox and shelves of self-help books. With each scary headline, I wished I could engage everyone I met in conversation about this desire-to-destroy. If we could recognize it, feel it, claim it without shame, we’d have less reason to act on it. Months went by; anthrax scares became more scarce; 9/11 slowly faded from news stories. I had a family to attend to, and a schedule with little room to agonize over the roots of violence.

Still, each year as the anniversary of the World Trade Center horror neared, the image of bowing in a public place emerged once again. But I didn’t follow through.

Until one day a lump in my left breast brought the possible diagnosis of cancer. Two weeks later, what looked like pathology turned out to be healthy tissue. But during those two weeks of contemplating my mortality, I had a surprising realization: one of my deepest regrets was that I never made it out into the street with my sign.

Well, okay. Fine, I said to myself. If this is what I need to do, I’ll go. The local art supply store had a piece of poster board just the right size; my older daughter had a box of charcoal pencils; and in the corner of the attic I found the easel I actually bought several years earlier for just this purpose. Sunday morning the easel stood in the middle of the living room and thick black curves of charcoal declared: “I Bow to the Power of Good in Me and in You.”

Later in the day with my embarrassed and impressed daughters in tow, I drove to the Village Green in Woodstock, N.Y., where we live, for my first bowing gig. Opening the trunk of the car, feeling my fingers curl around the cool red rod of the easel, I imagined what it might be like to reach not for an easel and a cardboard sign to speak your truth, but for a trunk full of explosives.

Minutes later I stood on an empty sidewalk in the middle of town, the easel with the sign next to me. I bent at the waist, my eyes half closed, repeating the same motion over and over again for twenty five minutes. Intermittently the mind would interrupt, “This is nuts.” But it didn’t stop me. Part of me knew that not only was this an exquisitely sane thing for me to do, it was as though this simple act of lowering my head and upper body was the most eloquent expression of something I’ve been trying to say all my life.