Dave Parker spent 19 years in the major leagues, racking up three Gold Gloves, more than 2,700 hits, two batting titles, seven All-Star games, two World Series rings and the 1978 MVP Award.

As part of the “We are Family” Pittsburgh Pirates, Parker was an athletic, flashy outfielder who excelled on offense and defense. And in our era, when Francisco Lindor signs a contract for $341 over 10 years, it’s worth noting that Parker was the first athlete to earn a million dollars a year.

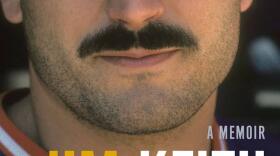

Parker was also part of a dark baseball chapter, the Pittsburgh drug trials, when he admitted using cocaine in the late 1970s and arranging its supply to the clubhouse. Parker is the author of the new memoir "Cobra: A Life of Baseball and Brotherhood."

We're speaking right around Major League Baseball’s opening day. What kind of memories do you have of opening days? And what kind of feeling does this time of year bring for you?

Well you get the urge to play this this time of year. You know, because baseball is getting close. And it's been mentioned on every news program, every sports program, so I get a little antsy right now.

When you were a player, what kinds of things did you have to do to get ready for the start of the season?

Just point me to the field. I was one of those guys that couldn't wait to get back out there. You know, you've been away from it for some months and you're dying to get back.

Did you like to work out a lot in the winter?

Yeah, I used to play racquetball and lift weights. And then my running.

Who would you play racquetball against? That's not a fair matchup.

Well, I played open. I was almost a pro. So I played some mean racquetball.

Were you able to play any during the baseball season? Or once it was April, did your focus completely shift?

Well, I gave it up when the season started. I was pretty physical and on the court and I didn’t want to get no injury to take me away from baseball.

You were such an athletic player. You were good at many different tools in in baseball. Was there a particular part of your game that you took pride in over other parts of your game?

Running the base hard every time. I always ran 100% to first base goes where the ball was hit. And I took pride in that. That's one less thing that a fan can say about you as a player when you don't hustle. And I took pride in hustling and being identified as the guy that did that.

Where did you learn that?

It came from the neighborhood. You know, I played baseball in my neighborhood, and it was a sports oriented neighborhood. And you had to come out and play or be shunned.

Does it bother you to see some stars in baseball not run out ground balls and things like that?

Yeah, I hate the fact that they're not fundamentally sound. They throw to the wrong base. Miss the cutoff, man. Don't hustle. You know, that bothers me.

There been a lot of changes in baseball, a real emphasis on home runs or strikeouts. Getting ready to speak with you, I was thinking back on the era that you were starring in and that kind of style of baseball has really changed. There's not a lot of base stealing, hit and run getting, you know, runners in motion, that kind of thing. Do you regret seeing that change in the game?

I don't mind seeing it, because I'm into cutting and slashing, dipping and dashing. That’s the kind of player I was.

If you don't mind me asking, how is your health these days? You've been public about your Parkinson's disease and your efforts to fight it and to fund research into Parkinson's. How are you feeling?

Well, I'm having good days, bad days, just like everybody else. My bad days, you just got to play the hand that’s dealt. And I know that it's something that I got to deal with for the rest of my life. And that's why I'm working with my foundation to try to raise money for research.

If this is too personal, just tell me and I'll move on to something else. But I'm wondering for somebody who was known as such a world class athlete as you, when you were diagnosed with Parkinson's, did you have to rethink kind of your own identity and who you were?

Well, I knew I was faced with something that I couldn't get around that was going to be a part of me, something that I had to adjust to, and in slows you down. So you had to make adjustments that way. I had to deal with my kids and my wife on a day in and day out basis. So, you know, I mean, I had all that to deal with. And it was something that I had to take on as a husband and father and a citizen.

You mentioned that you have good days and bad days. What are your good days like now?

It's going out without having Parkinson’s slow you down. You know, because it slows you down. And you make that adjustment every day. And good days, I'm not slowed down as much.

So I want to go back to early in your life for a moment. You mentioned learning how to play hard and run balls out in the neighborhood. Your original dream was to play football at Ohio State and baseball was kind of a backup plan, amazingly. Do you regret the fact that you weren't able to play at Ohio State for Woody Hayes, which was your first dream?

Well, you regret it because that was the plan. All of that was a plan for me. And I didn't have an opportunity to do it. Because I had a knee injury my senior year in high school that changed my whole life. But I couldn't play 19 years of football. And I see these guys that are 320 pounds running 4.5 4, you know, make me think that I'm in the right profession.

How did you end up making the change to baseball, because you were a multi-sport star in high school?

Well, baseball was my second sport. That was the one that I loved secondly to football. And I was good at it. I caught in high school. Pitched, played shortstop. So baseball was just a natural thing to return to.

How was your transition to the major leagues? I think in the time when you played a lot of times it was rough for rookies and the veterans could be kind of hard on new players. But you were so talented. What was your transition to the big leagues like?

I was supposed to be there. It was natural. They weren’t hard on me because I was 6-5, 225 pounds. I didn’t have no problems with that. And I felt that I should have been there, the big leagues is where I should have played. I should have been in the big leagues at 19 years old.

How are you able to stay in the league for as long as you did?

Well, I did the fundamentals. You know, and I was instrumental to the young players. I worked with young players, taught them how to be major leaguers. So I did the small things, and extended myself to players, young players. That was one of the keys to my success as an aging player.

In your prime when you played with the Pittsburgh Pirates and the “We Are Family” team that people probably remember, that team was very famous for its diversity and for its style of play. What made the Pittsburgh Pirates of that era so good?

Well, we played hard. And we had a theory on hitting first pitch fastball. You know, we're looking for the first pitch fastball, because we had a theory that the pitcher tried to get ahead with his first pitch and the fastball is the ball that he can control, more so than any other pitch he had. So we know first pitch fastball and when we got it we took advantage.

So you would be going up there ready to swing on the first pitch and not trying to work a deep count necessarily depending on how that pitch came in?

Well, if the fastball was in the zone, we look in the zone for the fastball. And then if it was there, we jumped all over it. So that was the Pirates’ theory. And it worked, because we would give up four or five games early in the season. And have to word towards. And we used to give up a lot of games, but we always came back.

You guys were known for being ultra-competitive. Where did that come from?

Just the nature of the team. Clemente, Stargell, myself. We just played the game hard. We never thought we were out of it. And Chuck Tanner, came over and was basically that type of manager.

Can you talk a little bit about what Willie Stargell was like as a teammate? It seems like, based on your book, a lot of people kind of looked to him to be the leader and to set the tone.

Yeah, Willie was the leader. He was the senior statesman. He was like a father, second to Chuck Tanner. And Willie was the leader. And I was the sergeant at arms. I took care of things that he couldn't take care of.

What would you do?

I would be hard on a player that didn't play at 100%. I took care of all the nasty stuff.

Does every team need somebody to do that?

You need to have an individual that govern themselves, you know, then that's up to the player. And you definitely need a couple guys on the team that help people govern themselves.

I know you've also been very interested in the percentage of Black players who are in Major League Baseball, which has been on the decline since your era. And it's been identified as a real problem for Major League Baseball,, you know, young Black stars are going into other sports. How do you turn that tide around in your mind?

Well, baseball’s gotta extend itself to the Black neighborhoods, Black colleges to extend themselves to recruiting these players, making the all-star game something that will attract Black you. There’s a host of things they can do. Basketball do a heck of a job getting Black youth to the game and presenting events that they can participate in. So you got to extend yourself as a sport.

I also think you were known just for being very cool. You were known as a cool baseball player. You were good. You were a popular quote for reporters, because you are so funny and quick-witted. And I'm kind of wondering if maybe it's partially marketing too. You know, it's hard to name a Black superstar in Major League Baseball today for the average sports fan.

Well, I'm available.

Are there any players particularly you see, in today's game that you identify with, either in terms of, you know, persona, or the way they play the game?

You know, I really can’t pick out one. You know, it's been a different animal. Baseball has altered itself since I played. So I really don't have a player in the major leagues that I can pinpoint as an all-around player.

As we speak, the Mets shortstop Francisco Lindor has signed a contract for $341 million over a decade. The reason I bring that up is you were the first athlete to average a $1 million annual salary. And it may be hard for people to imagine today, but you took a lot of hate over that salary and the free agent contract that you signed, a five-year deal. Does it just seem crazy to you looking back that that was such a controversial thing in sports and in your career?

Well, you always pay a price for being the first and I was the first at a time when the city that I was playing in was suffering industrywide, steel industry, coal industry, and they just couldn't identify to a player or making a million dollars a year. And I paid the price for being the first and all these guys that's reaping the benefits of these $300 million, $250 milion, I'm waiting for my 10%.

You haven't had any offers to cut you in, huh?

That's right.

You're sort of lighthearted about it. But you really did take a lot of hate mail and stuff, didn't you?

Yes, I did. It kept me from participating in the victory party of the World Series. I just couldn’t go to it, because I had received all the hate mail, been booed the whole season. And I decided not to go. But if I had to do all over again, I probably would.

Did it put some extra pressure on you knowing that you were making the money you were making, just in your own mind?

Well, I thought it was foolish to victimize a player for being rewarded for his achievement. And I had a hard time dealing with that.

But everything is cool with you and Pittsburgh now, right?

Yeah, I'm a Bucko. I’m still a Bucko.

If you don't mind me asking, what's your outlook health-wise?

Well, I’m going to live as long as I can. Parkinson’s is something that is gonna be with me the rest of my life. And I'm just going to live the best quality life I can.