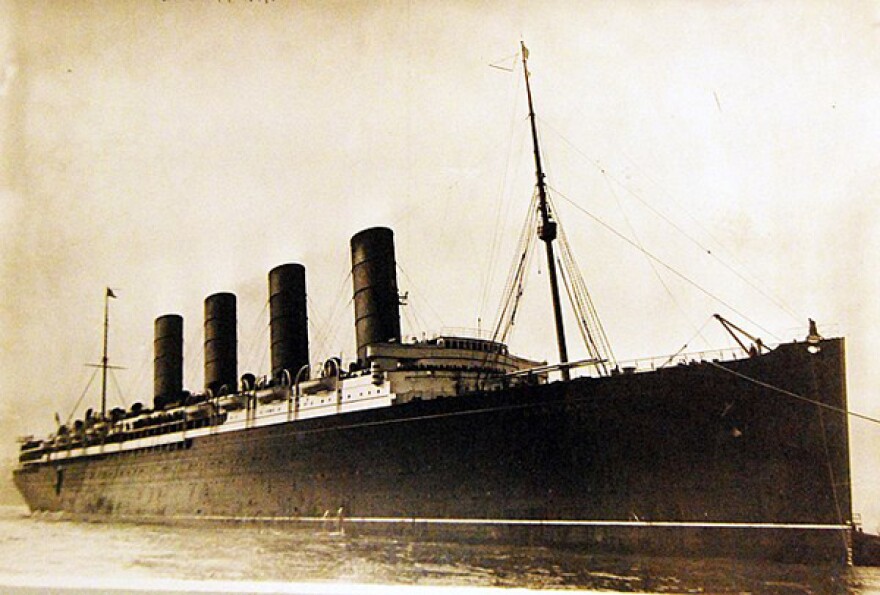

The ocean-going liner Lusitania was torpedoed in 1915, and it sank in 18 minutes. Just under 1,200 desperate American and European men, women and babies drowned – dragged into the Atlantic ten miles south of Ireland. There were 764 survivors, saved by assorted fishing boats from County Cork. [Ref.2, Ch.1]

Fifty years earlier, in 1864, the first ship recorded as torpedoed was the Boston-built Housatonic that had sailed down to South Carolina to take part in the blockade of Charleston. That was a large and beautiful ship – 200’ long and 40’ wide – and was sunk by a primitive torpedo sent from the iron submarine, the Hunley – which itself sank in the explosion.

Right now, as of May 2019, the USS Abraham Lincoln, an aircraft carrier bristling with F-18 jets, and accompanied by destroyers with guided missiles, is near the narrow Strait of Hormuz, not far from the skyscraper city of Dubai. Iran lies opposite, and the Iranian Guard has said that its short-range missiles could sink the ship. One is reminded of the 19th century Norwegian fairy tale about the three Billy Goats Gruff who have to cross the bridge that is guarded by a troll threatening to eat them if they try to pass. ‘Who goes there?’

The Lusitania was a fast passenger ship similar in size to the Titanic, which had hit an iceberg two years earlier (1913). These magnificent liners had ballrooms, sumptuous dining areas, smoking rooms, teak furnishings, wireless telegraphy, electric lights and lifts. In 1914, war had been declared between Germany and England (and involving other alliances) and while England had tried to blockade supply ships headed for German ports, Germany had drawn a blockading circle around the British Isles, inside which U-boats would attack all allied shipping deemed as a threat. In Washington, notices had been given out by the German Embassy that any such shipping inside that circle could be torpedoed. America was not in the war then, yet one might ask why so many Americans, including Alfred Vanderbilt, [owner of the Great Camp Sagamore in the Adirondacks] chose to embark in New York for such a dangerous trip. True, the Lusitania, holder in that era of the Blue Riband for fastest transatlantic crossing of just under six days – averaging 29 mph – had regular scheduled sailings to Liverpool, England, and many perhaps did not take the risk seriously. Fast liners could outrun and evade or ram submarines, if they were able to detect them.

Young Captain Schwieger’s submarine, the U-20, carried seven torpedoes. During the month of May he had been patrolling west and south of Ireland. On May 5, 1915 he had sunk the Earl of Lathom (a 3-masted schooner), and early the next morning the Candidate (a 6,000-ton cargo ship on its way to Jamaica). The same afternoon he had also sent its sister ship the Centurion (on its way to Durban) to the ocean floor.

He encountered the Lusitania the following afternoon – May 7, 1915.

According to a survivor, Vanderbilt was last seen putting life belts on little children.

The Lusitania now lies 300 feet down in the Atlantic, and the salvage rights have been bought by a private investor. Dives so far show it was carrying ammunition [ref.1 p.389].

Schwieger’s U-20 went on sinking ships, including the Hesperian, a 10,000-ton liner bound for Montreal. The next year he ran aground near Denmark, and was given command of a newer submarine, but met his end when it slammed into a mine in 1917.

As for the 1864 Hunley, that was raised and is now in its own museum in North Charleston, S.C.

Let’s hope that there will be no sunken Abraham Lincoln to raise from the Persian Gulf.

References:

1. “Lusitania” by Diana Preston; Walker Publishing Co, 435 Hudson St, NY, NY 10014. (2002.)

2. “The Lusitania Disaster; An Episode in Modern Warfare and Diplomacy”, by Thomas A.Bailey & Paul B.Ryan; The Free Press, a division of MacMillan Publishing Company, Inc; 866 3rd Ave, NY, NY 10022. (1975)

David Nightinglale is an emeritus professor of physics at SUNY New Paltz where he taught for 31 years. His first novel, The Centauri Settlement, is produced by TheBookPatch.com .

The views expressed by commentators are solely those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect the views of this station or its management.