Editor's note: NPR's Corey Dade recently traveled to New York to interview the Rev. Al Sharpton about the unusual arc of his checkered career, from pugnacious street fighter for racial justice to savvy insider with ties to CEOs, a successful television show and the the ear of a soon-to-be second-term president. Click on the slideshow above to see a day in the life of Sharpton and hear more about how he juggles it all while running a civil rights organization with 40 chapters across the nation, hosting his own radio show, and appearing on PoliticsNation — all on the same day.

The Rev. Al Sharpton has spent nearly all of his adulthood in the spotlight, earning both praise and condemnation. The 58-year-old Sharpton, whose role in the Tawana Brawley case first made him a national figure a quarter century ago, has been called a race-monger, anti-Semite, shameless self-promoter and a shakedown artist who has used the threat of protest to extract corporate donations for his civil rights organization, National Action Network. His conversation with an undercover FBI agent posing as a drug dealer was taped as part of a 1983 sting operation — but no charges were filed. He was indicted for tax evasion and fraud, and then acquitted. He was stabbed by a white man before leading a march.

He's also respected for his commitment to nonviolence and asked a judge for leniency for the man who stabbed him. He brought national attention to the "driving while black" form of racial profiling, which led to police reforms in many cities. He broke ranks with fellow black pastors to support gay marriage and denounce homophobia within black communities.

His protests of the police investigation of the fatal shooting of Florida teenager Trayvon Martin helped lead to a review of the state's "Stand Your Ground" self-defense law. And his fight against state voter-identification laws, which opponents feared would disenfranchise blacks and Latinos, helped mobilize minorities and lead to record black and Latino turnout in the 2012 presidential election.

Along the way, his career has given rise to a host of rumors, falsehoods and truths both unexpected and unflattering to Sharpton. In an interview with NPR, Sharpton addressed several of the more enduring facts and fictions. Here are his positions on some of the best-known aspects of his life:

Was Sharpton James Brown's Tour Manager?

That's fiction, Sharpton says. It is true that Sharpton had a close relationship with the legendary singer and revered him as father figure. Brown, who died in 2006, had filled the void created in Sharpton's life when his father abandoned the family when he was a boy.

Sharpton and Brown met in 1973 following the death of the singer's 16-year-old son, Teddy, in New York. Teddy had moved there from Georgia and joined a youth outreach organization run by Sharpton, who also was 16. After Teddy died in a car accident, Brown performed a memorial concert in New York and donated the proceeds to Sharpton's fledgling organization.

Upon learning about Sharpton's family situation, Brown began to mentor the young preacher. From Sharpton's late teens to his mid-20s, he often toured with Brown.

"[But] I never was his road manager," Sharpton says. "I was still just a kid. He would tell me, 'I don't want you in entertainment.' "

To Brown, Sharpton owes much: funding for his activism; Sharpton's former wife, who was a backup singer for Brown when they met; lessons in showmanship and self-promotion; and, of course, Sharpton's hairstyle (Brown's idea, Sharpton says).

Does He Really Have Ties To Sen. Strom Thurmond?

That's a fact. Sharpton and the late longtime South Carolina senator aren't blood relatives, but the truth is just as provocative. Two of the most prominent figures in the 20th century racial divide — one a civil rights leader, the other an icon of segregationists — trace their ancestries to the same slave plantation in South Carolina.

Sharpton's paternal great-grandfather, Coleman Sharpton, had been a slave owned by Julia Thurmond Sharpton, a first cousin, twice removed of Strom Thurmond, according to genealogists' research.

"It was probably the most shocking thing in my life," Sharpton has said of the discovery.

Sharpton says he has visited the plantation in Edgefield, S.C., on Sharpton Road.

"In the story of the Thurmonds and the Sharptons is the story of the shame and the glory of America," Sharpton said at a 2007 news conference about the findings.

Did He Undergo Gastric Bypass Surgery To Lose Weight?

That's fiction, Sharpton says, although Sharpton has lost 110 pounds in two years.

Through the 1980s and 1990s, Sharpton's girth, often stuffed into unflattering tracksuits, was as much a part of his persona as his tactics.

His first significant weight loss, of nearly 40 pounds, came from a 43-day hunger strike to protest the U.S. naval bombing exercises on the Puerto Rican island of Vieques in 2001. Sharpton had been in a federal prison at the time after being arrested at a demonstration on the island.

Sharpton regained some of the weight during his 2004 presidential campaign, particularly by dining late at night during his rigorous travel schedule. "To eat and lay down on that food — the worst thing in the world," he says.

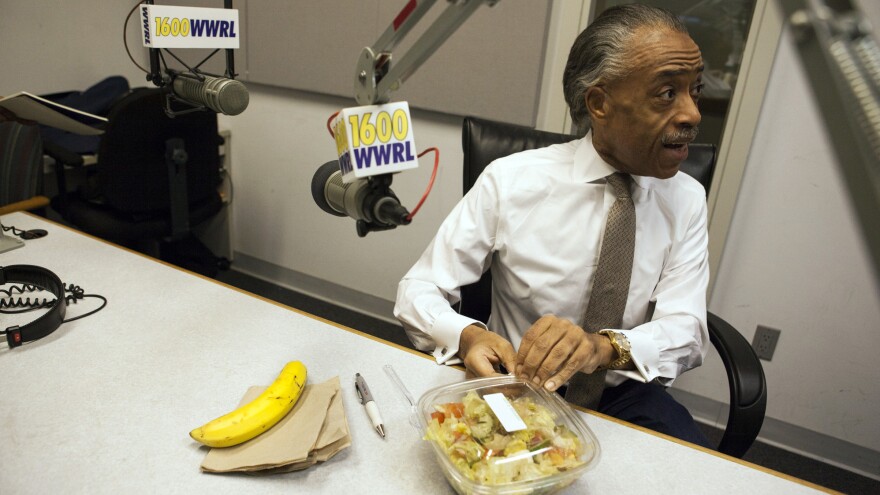

Sharpton says he tried several diets but "none of them worked." Finally, he decided to go almost entirely vegetarian. He eats fish, usually sea bass, on Saturdays. Otherwise, he follows a strict regimen: two pieces of toast about 5:30 a.m., and then a treadmill workout; a salad, banana and hot tea for lunch about 12:30 p.m.; two pieces of toast and tea in the afternoon.

"I don't eat anything after 6 o'clock," he says.

His staff and others close to him say they are amazed, and sometimes worried, that a 58-year-old man who eats so little food can maintain his usual pace of 16-hour days, usually seven days a week. He travels constantly, runs a national organization, hosts daily radio and television shows, and makes appearances well into the night. But, Sharpton says, "I don't even feel it. It's normal to me now."

The tracksuits are long gone. "I've had to get a whole new wardrobe. I've got a guy on Soho who makes Italian suits well, especially those 'skinny pants' y'all call them."

Did He Help Tawana Brawley Make Up Her False Rape Accusation?

That's pure fiction, Sharpton says of one of the most incendiary episodes of his life. The 1987 case of the 15-year-old girl brought him notoriety that he may never overcome in the minds of some Americans.

Brawley, who is black, claimed she'd been assaulted and raped by six white men, some of them police officers, in a town about 70 miles north of New York City. Sharpton was among the girl's most vocal defenders. He made his own controversial accusations, the most outlandish of which was that the prosecutor in the case had participated in Brawley's rape. (The prosecutor, Steven Pagones, later won a $65,000 defamation judgment against Sharpton, who lost on appeal.)

A grand jury declined to bring indictments after determining that Brawley's claims were a hoax. The case inflamed racial tensions across New York and nationally, and Sharpton was roundly criticized as the instigator who had gravely overreached.

Over the years, critics, politicians and news media have demanded that Sharpton apologize for his role and publicly condemn Brawley. But Sharpton has refused, perpetuating the ill will that many still hold for him.

"What do I have to apologize for? I believed her," Sharpton says. He says he regrets having resorted to "name-calling" against Pagones and that the case taught him to refrain from personal attacks in his activism. But he doesn't regret having stood for Brawley, he says.

Did He Incite The 1991 Riots In Crown Heights, Brooklyn?

Sharpton also says that's fiction, although some of his strongest critics hold a different view.

A car accident in which a Hasidic driver killed 7-year-old Gavin Cato, who was black, sparked outrage. Rioting erupted and lasted for three days, during which a rabbinical student, Yankel Rosenbaum, was fatally stabbed in an attack by a group of young black men. An estimated 43 civilians and 152 police officers were injured.

Against the objections of New York Mayor David Dinkins, who sought to calm tensions, Sharpton led a march of some 400 protesters through the neighborhood. He and his followers chanted "No justice, no peace." Some marchers were heard yelling anti-Semitic epithets. The march ended without incident.

In a eulogy at the boy's funeral, Sharpton criticized Jewish merchants in Crown Heights for selling diamonds from apartheid South Africa. He also said: "All we want to say is what Jesus said: If you offend one of these little ones, you got to pay for it. No compromise, no meetings, no coffee klatch, no skinnin' and grinnin'." Among the banners hanging to commemorate the boy, one read "Hitler did not do the job."

Many Jewish leaders and others say Sharpton incited the violence or at least perpetuated hostilities. They disapproved of his decision to hold the march on the Jewish Sabbath. Some already had criticized him days before the riots for remarks he delivered at an unrelated rally in Harlem: "If the Jews want to get it on, tell them to pin their yarmulkes back and come over to my house."

Sharpton rejects the blame. He says he was at his home in New Jersey — having been nearly fatally stabbed by a white man months earlier — when the violence started. He says he got involved on the second day of the riots and hadn't yet known about Rosenbaum's stabbing.

Last year, marking the 20th anniversary of the incident, Sharpton wrote an op-ed in the New York Daily News in which he admitted "our language and tone sometimes exacerbated tensions and played to the extremists." He said, "I have grown. I would still have stood up for Gavin Cato, but I would have also included in my utterances that there was no justification or excuse for violence or for the death of Yankel Rosenbaum."

Rosenbaum's brother, Norman, responded with his own op-ed in the Daily News rejecting Sharpton's recollection as "egregiously distorted and sanitized." He faulted Sharpton for failing to apologize for his "reprehensible" conduct: "Based on everything we have seen and read, Sharpton never called upon the rioters to stop their anti-Semitism-inspired violence. He never called on the rioters to go home. To the contrary, he stirred them up. And three days of anti-Semitic violence became the Crown Heights riots."

Was MSNBC's 'PoliticsNation' Show A Quid Pro Quo?

That's fiction, say both Sharpton and Comcast, MSNBC's parent company.

MSNBC's decision to name Sharpton as host of its daily 6 p.m. hour in August 2011 surprised many observers because of his controversial history and lack of experience as a television journalist. His hiring came after Sharpton and other black leaders a year earlier had lent pivotal support to Comcast's successful bid to acquire NBC Universal, the former parent company of MSNBC.

One theory was that the network gave Sharpton the show, PoliticsNation, as a reward for his endorsement of the merger.

"Sharpton has a long and well-documented history of leveraging his civil-rights profile for his own benefit," Daily Beast writer Wayne Barrett, a longtime critic of Sharpton, noted in an article last year. "Grabbing a prime-time anchor spot in exchange for cheerleading for a controversial merger would be the capper on that career."

Comcast said in a statement last year that company executives "pledged from the day we announced the transaction that we would not interfere with NBCUniversal's news operations, including at MSNBC. We have not and we will not."

Sharpton says there was no connection between his support for the merger and his hiring at MSNBC. He says he and MSNBC hadn't discussed any potential show before he signed the agreement and at the time there were no available time slots on the network.

He says the idea for a show came from Paula Madison, then the executive vice president and chief diversity officer for NBCUniversal. She envisioned Sharpton hosting a weekly program similar to the CNN show hosted by civil rights leader Jesse Jackson in the 1990s. Sharpton says he pitched the idea to MSNBC President Phil Griffin, who rejected it before eventually deciding to hire him as a daily host.

Another theory, from some conservatives, is that Sharpton was hired by the left-leaning cable network because of his close relationship with the Obama White House. Sharpton says, "If Obama had that kind of power, he would have gotten [fellow MSNBC show host and Republican] Joe Scarborough off the air instead of me on it."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.