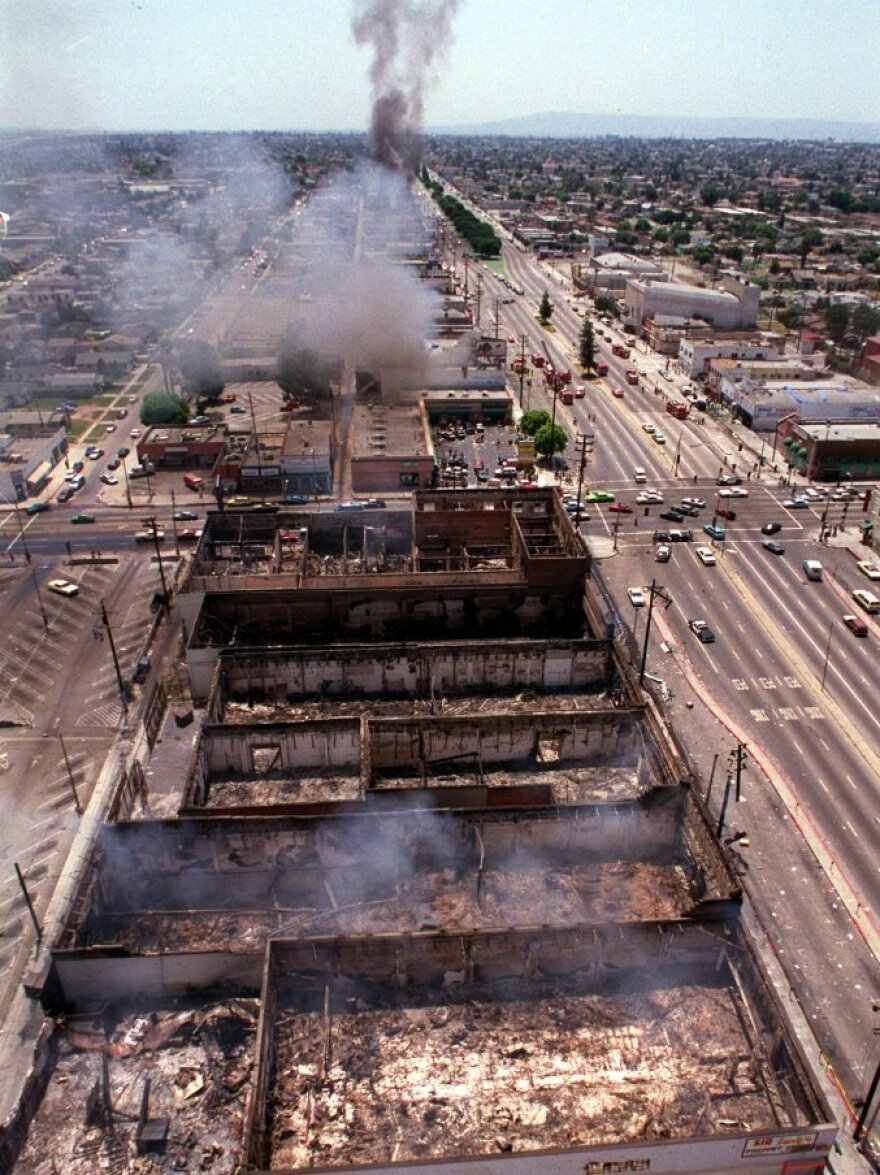

Twenty years ago Sunday, Los Angeles erupted into destructive riots after the verdict in the Rodney King trial. The violence lasted six days and left more than 50 dead and over $1 billion in damage. NPR's Karen Grigsby Bates remembers; she lived in the one of the neighborhoods that went up in flames.

Several years ago, I interviewed Karl Fleming for the 40th anniversary of the Watts riots. He was a veteran journalist who'd covered the civil rights movement in the in the 1960s for Newsweek.

Fleming had left the Deep South when his editors decided he needed to be rotated out of there. Riding toward Watts, he told me he was shocked to discover that while he'd left the Deep South for L.A., he hadn't escaped it.

"These guys, these cops, rolled around with the windows rolled up looking nothing less than kind of an occupying army in a hostile and foreign country," Fleming said. "They had a long record of humiliating people, black people, pulling them over and doing what they called 'proning' them on the ground."

In the early '90s, before Rodney King's beating became worldwide news, that's how much of the Los Angeles Police Department interacted with many of L.A.'s black residents, from gangsters to preachers.

It's why you'd hear N.W.A's 1988 anthem, "F--- tha Police," blaring from all kinds of cars in black L.A., from busted-up hoopties to a fully-loaded Mercedes. Two years before Los Angeles went up in flames, you couldn't go a day without hearing some part of that song if you lived at my end of town.

VH1's documentary, Uprising: Hip Hop and the L.A. Riots, feels about right. Many of the major players were interviewed, including civil rights attorney Connie Rice, who'd been arguing for police reform for years. She told VH1 producers what she was thinking when she saw the King tape.

"The thing that was dawning on me as I watched it was, 'Is this the thing that will finally blow LAPD open?'" Rice said. "Will it finally be enough for them to finally see what everyday African-Americans had been talking about for years, and have been ignored?"

It wasn't for the jury in suburban Simi Valley when they acquitted the four white police officers in the beating trial of black motorist Rodney King.

By late afternoon on the day the verdict was announced, reaction had become violent. By early evening, I could stand on my front porch and smell the smoke from fires just a few blocks away. The next morning, I had a flashback from my New England childhood, except the sidewalks and lawns and car roofs weren't covered with snow, they were covered with ash.

It wasn't just my neighborhood; the fires had spread beyond the confines of black L.A. to places that normally don't have much to do with my end of town.

"There were people in Beverly Hills who were nervous; people in the big pink hotel on Sunset that were nervous," recalls entertainer Arsenio Hall, "because the riot wasn't confining itself just to the ghetto."

If you lived in or near the ghetto, you could forget about services. For the first few days, there was no mail. The shelves in what few grocery stores that existed were quickly denuded. The first new grocery to open in the neighborhood in 30 years was gated and shut tight as soon as the verdict became public.

I took a trip across town with a friend to buy groceries. Everything was outwardly calm and intact, but inside panicked people piled their carts high, stockpiling for an Armageddon that was miles away. On the way home, we marveled at how life could be so unchanged in one part of L.A., while everything had changed at our end.

VH1's documentary captures all the energy and anger and destruction that occurred in the six days that the riots raged, and unlike a lot of reporting at the time, it does it from a grassroots point of view. It's worth watching and considering, because as students of history will tell you, uprisings are cyclical.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.